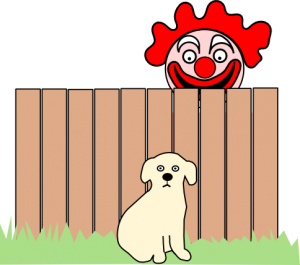

I admit I’ve never been particularly fond of clowns. I find them neither funny nor sad. Just weird. For some people though clowns can be outright scary. Some people are afraid of clowns. And this unfortunate fear even has a name: coulrophobia. Some experts think the fear of clowns is linked to the uncanny valley effect, a fascinating phenomenon which describes how a “human-but-not-quite” appearance makes some people feel uncomfortable or repulsed. When I watched a news report on a clown convention the other day, showing a room packed with hundreds of clowns, I could only imagine the nightmarish horror this would create in a coulrophobic person. And what on earth does that have to do with puppies?

Well, thinking that clowns are weird is of course a personal matter but clowns certainly look weird. They typically transform their faces with heavy makeup to create a frozen emotional expression such as a wide laughing mouth, raised eyebrows and other exaggerated features. We humans are able to “look beyond the mask” (even those who are phobic) – we still know there’s a human underneath – but what about other animals? Can dogs automatically assign a disguised person to the broad category of human? Do they even have a category of human?

Fear and survival for the modern companion dog

Dogs, just like many other animals, learn crucial lessons about the world they live in as they grow up. Everything they experience during the early stages in life – sights, sounds, smells, other animals, plants, objects etc. – will be catalogued in their brains as familiar. Most of these familiar things will fall into the category of safe (irrelevant, harmless, good or desirable) while some may be considered potentially dangerous (to be avoided). Anything a dog does not experience during early development will generally be met with caution, suspicion or fear later in life. This makes perfect sense from an evolutionary perspective: You better believe the clown is going to eat you before your trusting nature makes sure you’ll never get another chance.

But, if a dog’s early developmental environment is so impoverished that almost everything they come across later in life falls into the unknown category, their quality of life will be greatly diminished. There will be clowns everywhere. It is one thing to experience stress once in a while when faced with a real or perceived threat but to live in a constant state of anxiety creates a serious mental and physical health risk. Imagine you can’t leave the house because there are scary clowns lurking on your doorstep. Imagine that sometimes they even come inside and you are powerless to stop them. And worse, imagine that the only person you thought you could trust seems to conspire with those clowns against you. This is what fearful dogs must experience whose humans fail to understand their anxieties.

Domestic dogs, and in particular companion dogs, have the best chance to succeed in a human world if they believe that world is safe. Dogs who are not fearful of people, other dogs and whatever life throws at them will hopefully never feel the need to defend themselves. Our society has zero tolerance for dogs defending themselves and dogs who growl (“leave me alone”), snarl (“I mean it”) or bite (“I told you”) can quickly end up with a one way ticket to the vet.

So the goal has to be that there is very little left in the unknown category when a puppy starts to emerge from their sensitive period of development some time between 12 and 18 weeks of age. Given that puppies generally come to live with their families at no younger than 8 weeks of age this may only leave a small window to socialise a young dog and expose them to as many new and positive experiences as possible (known as puppy socialisation).

The ideal puppy graduates with an “I ♥ humans” badge

It seems dogs are perfectly able to form categories based on visual information but they may not generalize as well as we do, at least when it comes to variations of human appearance. One favourite and often repeated example of incomplete puppy socialisation is the fear of bearded men. I think we can be quite sure that dogs don’t have an issue with beards per se, unlike pogonophobic people (yes, believe it or not, there is a fear of beards). Maybe they consider bearded men as a new (unknown) category. Or maybe they recognize bearded men as humans but feel uncomfortable because “something is not quite right”. The important message to take away from this is that puppies need to have friendly experiences with more than just a human in order to strike humans off their list of potentially dangerous.

The human species comes in all sorts of shapes, sizes, colours and camouflage. We differ in age and gender, the way we speak and the way we move. Clearly, we are a diverse bunch and modern technology has made us even more variable. Be it headphones, wheelchairs or snorkels, humans often have stuff protruding from or attached to almost every part of their bodies. Only a dog who has seen different versions of human appearance and locomotion as a young puppy will be untroubled by encounters with the human kind.

Does a dog have to like all people? No, and they probably won’t anyway, but at least we don’t want them to fear people. Unfortunately we cannot teach a dog to distinguish between good people and bad people. If a dog thinks humans are generally good news, we can confidently take the dog anywhere and invite people to our homes without worry that a particular person or type of person might trigger the dog to react badly. Yes, your dog might one day happily take a treat from a burglar instead of raising the alarm. But that’s nothing compared to dealing with an agitated neighbour at your doorstep because their child got bitten by your dog. A poorly socialised dog may make a good guard dog but they will probably spend their lives in relative isolation. That’s a sad fate for such a social species.

Puppy socialisation and beyond: we can always make a difference to our dogs’ lives

Puppy socialisation is hard work and it doesn’t happen by itself. It’s a proactive, well-planned and controlled procedure (for details see the resources below). But those early weeks in a puppy’s life simply cannot be wasted. How we treat puppies and what we expose them to makes a huge difference for the dogs, their families and the community they live in. Part of the responsibility rests on the shoulders of breeders and the regulating authorities. The rest is up to everyone who takes a dog into their home.

While the early weeks are super important for the puppy’s development, the need for socialisation doesn’t end once the sensitive period is over. Social skills can be lost and problems can develop over time if a dog lives isolated and without frequent exposure to other people, other dogs and the outside world. The first three months are the most crucial in terms of impact and long lasting effects, but every animal is shaped continuously by experiences throughout their entire life. We may not be able to repair damage done and opportunities lost during the sensitive period, but we can always try to maintain and possibly improve a dog’s quality of life.

It should be noted that there is of course always a genetic component to a dog’s behaviour. Some dogs for example are naturally wary of strangers or easily spooked by new things (neophobic) and not even the most extensive socialisation program can turn them into sociable and relaxed dogs. But we should always do as much as we can to make our dogs feel as safe and comfortable in their environment as possible.

RESOURCES

Note: The term puppy socialisation usually includes habituation (strictly speaking socialisation means learning to live with humans and other animals while habituation means getting used to one’s environment).

The PPG (Pet Professional Guild) and the ASPCA have good advice on puppy socialisation including checklists:

PPG Puppy Socialisation Info

ASPCA Puppy Socialisation Info

Range F, Aust U, Steurer M, Huber L (2007) Visual categorization of natural stimuli by domestic dogs. Anim Cogn 11(2):339-47

Visual categorization of natural stimuli by domestic dogs

And just in case you are now curious about the fear of clowns, here are some interesting links to articles on coulrophobia and the uncanny valley effect which have absolutely nothing to do with dog training:

History and Psychology of Clowns Being Scary

Why zombies, robots, clowns freak us out

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Sylvie Martin

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Sylvie Martin

ji can you share any advise on teaching early signs of anxiety to adults and children along with how important it is that children learn the importance of giving a dog space please?

Hi Terri-Ann,

Here are some resources on body language and dogs & kids which you may find interesting:

(nice youtube video on body language by http://www.thefamilydog.com)

http://www.livingwithkidsanddogs.com

http://familypaws.com

As a hard and fast rule, no one should approach an unfamiliar dog unless the dog is already approaching them to greet. When approaching a familiar dog and the dog leans away, flattens ears, looks stiff etc. the dog should be left alone. Also, every dog should have a space in their home (e.g. their bed or mat) where they can retreat to and be safe from being hassled or approached.

Dogs that suffer from anxiety need help in form of a proper desensitization & counterconditioning program (http://fearfuldogs.com is a great resource)

Hope that helps!