Did my headline get your attention? Before you ponder your dog’s devotion to you, let me say straight away that it poses an unfair question. It is unfair because a) it’s the type of headline that blatantly aims to trigger an emotional response and b) it’s unanswerable.

“How confident are you that the information is accurate?”

The purpose of a headline is to pique the reader’s interest and encourage them to read an article. Unfortunately, all too often, a headline can become a standalone source of information. As you browse your social media or the daily news, a headline catches your attention but you might not have enough time or interest to read further. Even if you do, maybe you only read the first paragraph or you quickly scan the article trying to extract the gist of the story. And if you actually do read the whole thing: How confident are you that the information you take away from it is accurate?

Here is a recent headline: “Dogs Prefer Tummy Tickles To Treats According To Science”. Note the addition “According To Science”. That should give us confidence that the information is correct, right? The thing is: This headline isn’t any more valuable than mine. It presents a lure to draw the reader in and nothing more. This wouldn’t be so concerning if everyone understood that – unless a headline describes an irrefutable fact such as “Federer wins Australian Open” – it rarely tells the whole story and it can even be misleading. Not that this is necessarily the intention of the author. It is simply the way headlines are created in order to compete for the attention of readers. Sure we can blame individual authors or the media as a whole, but it may be more helpful if we relied on ourselves to read beyond the headlines.

“The results cannot possibly justify a blanket statement such as ‘dogs prefer praise over food’”

As it turns out, there was indeed a recent study* that tested the neural responses (specifically, the activation of the ventral striatum, a brain structure that indicates the experience or expectation of something pleasurable) in 15 dogs when they were presented with either a promise of receiving food or a promise of social contact with their primary guardian. But the study is a little more complicated than simply giving dogs a choice between food and praise. And the results cannot possibly justify a blanket statement such as “dogs prefer praise over food”.

The current research into the emotions of domestic dogs through “awake canine neuroimaging” is extremely fascinating and I’m sure it will add to our understanding of the unique human-canine bond. But we are not doing our dogs – and ourselves – a favour, if we hastily draw conclusions from an experiment that tests the neural response of dogs to specific stimuli under very specific conditions and then hail this as a significant contribution to the practical application of dog training. A common problem with translating scientific studies for the public is the misinterpretation of the study results and this has certainly been the case here.

The possible practical value of the study (and hopefully more studies with larger sample sizes to follow) is the detection of differences in individual dogs and dog breeds in regards to their tendency for strong social bonding to humans. Those differences may help with the selection of dogs for certain tasks such as assistance and therapy dogs. Dogs who showed higher ventral caudate activation in the experiment when expecting social contact instead of food are possibly more suitable for jobs that involve close cooperation and bonding with humans. However, to conclude that praise would have a better or equal effect on the willingness and performance of dogs when we teach them skills or try to create positive emotional responses is not warranted.

“It is the history of reinforcement that determines a dog’s future behaviour. Make sure that history is stacked in your favour by using memorable, high value rewards.”

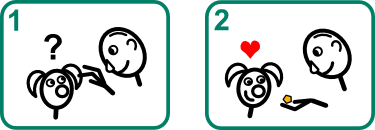

What a dog wants is influenced by many factors that continuously modify their current mental, emotional and physical state. The dog’s saturation with food, play, exercise and social contact is what largely decides the efficacy of a chosen reward or motivator at any given time.

In the neural response experiment the dog is alone in an environment away from the home they share with their human(s). In a typical training environment on the other hand a dog is either with their human or another person they are comfortable with (reward-based training wouldn’t work if the dog didn’t want to be there in the first place). The dog’s social needs are likely already met. In that scenario the trainer has to find out what the dog wants most at the moment. A motivator has to be potent enough to trump (apologies for using that word – it makes me cringe too) anything else that might be going on in the dog’s internal and external environment.

In a previous study**, which tested the responses of dogs (and hand-reared wolves) to food versus social interaction in a more realistic training setting, the results clearly indicated a preference for food over praise or petting. Even shelter dogs – who were deprived of human contact and could therefore be expected to experience social contact as highly reinforcing – responded better with food.

Before expecting your dog to perform behaviours for you “for free”, think about all the competing factors. Yes, your dog may waddle over to you for a belly rub when hanging out at home. But good luck consistently calling your dog away from their dog friends at the park or a possum in a tree with no other promise than that of a belly rub or praise.

It is the history of reinforcement that determines a dog’s future behaviour. Make sure that history is stacked in your favour by using memorable, high value rewards.

“Social contact is a dog’s right, not a reward. Social bonding between dog and human is the best foundation to successfully teach your dog skills.”

Hopefully your dog gets plenty of belly rubs from you anyway. Rather than using social contact as a reward for behaviour, it should form the basis for cooperation. Social contact is a dog’s right, not a reward. Social bonding between dog and human is the best foundation to successfully teach your dog skills. A happy and cooperative dog is more likely to show enthusiasm during training. You can control this enthusiasm – and hence the learning outcome – through potent motivators.

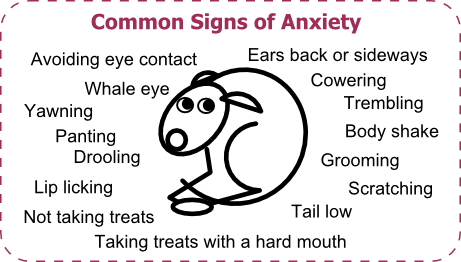

Headlines that dismiss the value of food in dog training are concerning because they pander to some people’s expectations that dogs should perform behaviours simply because of their devotion to us. They fuel the idea that using treats in training is a bad thing, that it “corrupts” dogs and that it negatively affects the dog-human bond. Nothing could be further from the truth. It would be highly detrimental if dog lovers avoided or abandoned food rewards in training due to the erroneous belief that praise or petting are suitable replacements. In fact, food rewards should be encouraged more and their value highlighted at every opportunity. No matter if you teach your dog a specific skill, modify a problem behaviour or want to help your fearful and anxious dog to feel better, dish out those tasty morsels, so your dog receives the best motivation and has the best chance to succeed in life.

REFERENCES

* Peter F. Cook, Ashley Prichard, Mark Spivak, and Gregory S. Berns.

Awake Canine fMRI Predicts Dogs’ Preference for Praise Versus Food. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience Advance Access first published online August 12, 2016 doi:10.1093/scan/nsw102

** Feuerbacher, E. N., & Wynne, C. D. L.(2012). Relative Efficacy of Human Social Interaction and Food as Reinforcers for Domestic Dogs and Hand-Reared Wolves. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 98, 105-129